Interview Date: April 19, 2006

Interview Place: 4307-20th Street, San Francisco

Interview Purpose: for WGBH’s The American Experience program titled Summer of Love. The program originally aired in San Francisco in April 2007, and is available from WGBH and on youtube.

© 2007 WGBH Educational Foundation who provided permission to present this transcript.

The transcript has been very minimally edited. It is the raw transcript, containing both material used and unused in the program. The “interviewer” is Gail Dolgin, the “male voice” is Vincente Franco. Lynn Adler was also involved in producing the interview.

Standard editing formats have been used. Brackets are editorial additions; ellipsis signifies deleted material. Pauses and video formatting were removed. Some of the interviewers’ questions were edited as they were hard to hear, but occasional discussions about questions, which shed light on how the answers were crafted, were retained.

Most of the paragraphing was designed for video editing. Some paragraphs have been revised, but many reflect that the interview is not “text”. It is spoken word. Punctuation was created and varies; graphics were inserted. Peter Berg never saw this transcript.

[Beginning of recorded material disk 1]

Interviewer: (laughter) Be serious.

Peter Berg: Do your own thing.

Interviewer: OK. We’re rolling.

Interviewer: To kind of just set the stage for us, give us a little background of yours. When you were born, where you grew up, what the culture of your family or the scene that you were growing up in was.

Peter Berg: I was born in New York in the late 1930s, and probably the foundational event in my life was moving to the South when I was six and becoming a spectator to Southern culture. Not a tourist, but a permanent visitor, and the biggest effect of that was to make me sensitive to racial division, economic division. I adopted a very political perspective. Maybe as a way to live there or maybe because our family was more liberal than anybody we were around. So I carried that with me until I left Florida and began looking for another place to live actually, and found it when I came to San Francisco when I was 17 the first time.

The Beat movement was in its last days. I hung around North Beach. I knew it during the time of the Coexistence Bagel Shop—if anybody knows the date of that. And there were bongo players on the sidewalk and that whole milieu, although I felt very distant from it.

I went to New York. I spent years in New York, living on the Lower East Side. Left the Lower East Side in 1963 (?) and came back to San Francisco. Stopped in. Went to Mexico for a month. Came back in culture shock, reverse culture shock at how cold the United States seemed to be.

I had spent years in the Civil Rights Movement, including college and New York. The early Civil Rights Movement, the second sit-in in Richmond, Virginia. Probably 1959. That whole period, late 50s, the early 60s. So I had a very political background.

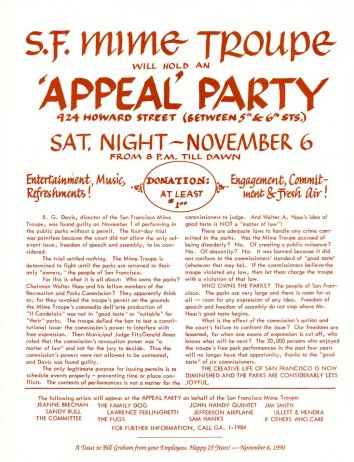

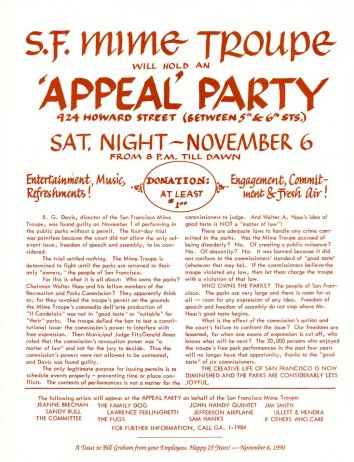

I worked here for a little while, and then one day walked into the San Francisco Mime Troupe—which we called Mime [Meeme- French pronunciation] Troupe at the time. You can tell the people that were there before 1970 because they all say Mime [Meeme] Troupe instead of Mime [Miime-English pronunciation] Troupe.—I told them I was a writer, performer, director, and they said, “Well, really? (laughs) Do it. Here is a five-act turgid play by Giordano Bruno, probably never meant to be performed, called Candelaio. It’s a philosophical treatise. Reduce it to three acts for a performance as a Commedia Dell’arte in the park, and we’ll believe you.” (chuckles) So I did that. And, by the way, I interviewed for that at the time that Bill Graham interviewed to become the business manager. The same day. I met him then. William Grajonca from the Catskills in New York.

Anyway, the play was written. Ronny Davis directed it. Luis Valdez, who founded Teatro Campesino in Delano [California] was in it. Other people were in it. But when we went to perform it in the park, because the Mime Troupe had deliberately not applied for a permit—to defy the city for various reasons, the police showed up. We knew they were going to show up. We invited the left, progressive people in the Bay Area from Berkeley to San Jose to San Francisco and Marin to come and be supportive, and a crowd of about 250 or 300 people showed up. Most of them activists. The police showed up. The director of the theater saw that the lead was going to get arrested. So he took his costume, stepped out on the stage, and the police arrested us [him].

It was an amazing event. It was staged. It was a staged arrest. The elements of it were—mentally, they were so strong to me that…it formed my whole consciousness from then on about theater because it was as though we had staged an arrest rather than staged a play.

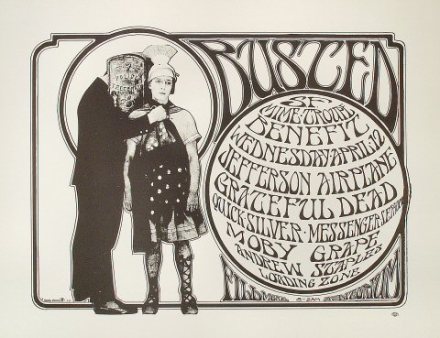

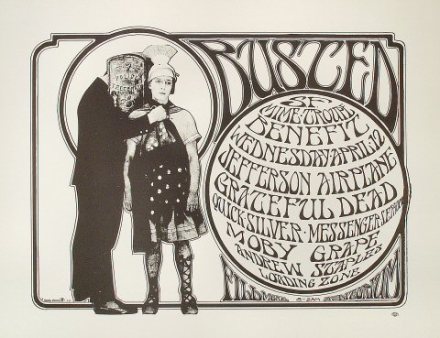

The play was the pretext for an arrest, but a lot of things could have been the pretext. Anyway, as theater, it certainly did what was called “breaking the fourth wall.” The goal of both Bertolt Brecht from a left direction and Antonin Artaud from an individualist direction was to break the barrier between theater and the audience. And this certainly did that. Regardless of what you want to call it. I mean, other things using theater could do this and have done it, but this did it in a very timely way. And that arrest became a public outcry. And as a result, Bill Graham thought of the idea of having a benefit to support the Mime Troupe, and that benefit became the model for the shows that he later did at the Fillmore Auditorium.

He didn’t know how to do that. [Bill Graham received]…a lot of suggestions. I suggested Allen Ginsberg, The Mothers of Invention, Lou Welch, the San Francisco poet. There were other groups that showed up. I think Blue Cheer, one of the early San Francisco sound groups, was there. And it was a huge success. This benefit became another piece of theater.

It was media theater, and because of who appeared at the benefit, we began breaking with the left culture and breaking over into the psychedelic culture. A lot of us were there anyway. A lot of the actors were, but the ideology of the theater [the Mime Troupe] was mostly new left—old left/new left—in transition. We were doing Brecht plays for example, Bertolt Brecht’s plays.

But that event certainly broke that down—began breaking that down. I think there were 5,000 people that showed up at our studio, which was just a small loft on Howard Street. They went around the block. The line went around the block. There were so many people that a means had to be devised to see whether people were coming in and out. So people were stamping hands for the first time, and a lot of firsts were accomplished there. I think Graham gave out apples, and that’s where the apples at the Fillmore Auditorium came from and maybe Apple Records, for all I know. At any rate, that was a phenomenal event, and then there was a second benefit.

And my mind started to drift from performing plays to creating events that would galvanize audiences—to turn them into participants rather than spectators and to not do this in a cute way. To me, “Happenings” in New York where people in the audience were given things and directed to do various things as part of the entertainment—that was cute. I wanted people to actually do something on the level of: protest the police arresting us in the park. And for this reason I wrote a play titled Centerman where American MPs beat a German prisoner of war to death over the course of the play. …

It’s from a story titled “The Dandelion.” The prisoner reaches for a flower and, by reaching out that way, the guard sees him as breaking ranks and beats him to death. And I decided to leave it like that without any other commentary. Just if someone is in that situation, this will happen to them if they try to break out of it.

Then we took this playlet and dropped it into social situations. And the first one was the Free Speech Movement rallies at Sproul Plaza. This is probably 1965. So we marched prisoners into the crowd. An MP brutalized them on the way in. People began shouting, “Leave them alone! Don’t do that to them! Why are you treating people like that? You shouldn’t treat people like that! It doesn’t matter what they did!” And the person [actor] is dressed as an American MP, military policeman, and he had them picking up cigarette butts and yelling at them and hitting them with the club. And then they began performing the play, and then the play ends with the prisoner being beaten to death. And the actor [the MP] directed the other prisoners to drag him off. So now they’re dragging a dead prisoner through the crowd at Sproul Plaza where people were outraged, screaming and yelling. And at the same time they were afraid to interfere. So it put everybody in the position of making a decision about what they would do. It gave them an experience. They experienced the moment of making a decision about protesting this or going along with it.

Well, we did more of these with the Mime Troupe, and then in 1966 one of the actors who had been in another one of these—my name for this was “guerilla theater”—had been another of these guerilla theater productions called Search and Seizure where ordinary people are picked up for drugs and interrogated by police. We did this in nightclubs. (laughs) Made everybody in the nightclub paranoid that they would get arrested because they [the actors] were just pulled out of chairs and thrown up on stage. Anyway, one of the actors was Emmett Grogan, and another was Billy Murcott, and these two had watched the Fillmore riots from a rooftop. And they were thinking that that was a revolutionary moment. That there was, in fact, a revolution about, at least, race relations going on in the United States and that there could be something like this for non-black, non-African-American, mainstream youth in the United States. And being actors in the Mime Troupe, they thought the first place they would strike was the door of the Mime Troupe, and they tacked up a list of complaints about the failure of the left. And one of the failures of the left was—the Mime Troupe. And it was signed “The Diggers.”

The Diggers were a 17th century English communal anarchist group who were formed because they were pushed off the land in England and forced to go to the cities. The digging they did was to dig up the lawns of the parks and the common pastures, called ‘the commons,’ in English cities, to plant crops because they had lost their farms, and they created a philosophy about living communally, living without rulers. If there wasn’t going to be a king, well, why should anybody rule? There was a lot of this during the early democratic movement … people like Rousseau in France and so forth. A whole history of anarchists’ thought. That if there aren’t going to be aristocratic rulers, then the rulers should be the people themselves but not necessarily through elected representatives, maybe through communal groups. That was the anarchists’ theme. And there were as many anarchists as there were democrats at the beginning of the so-called democratic movement.

At any rate, that was the name that Billy Murcott chose to sign this list of theses—all very dramatic. But by the end of the week, I thought, “This is a perfect way to do free provocative theater. A group called The Diggers who will have the goal, or have as their theme, that ‘everything is free’ and that people should be encouraged to ‘do their own thing’, be expressive.” So the street theater that we had been doing, the theater in the park which was free—all of this was free—was now going to be acted out as an alternative society where food, shelter, entertainment was going to be free, and the people doing it were going to be doing their own expression of that, without ideology. “The Diggers.” That’s what The Diggers would be.

And from my point of view, it was a largely theatrical enterprise, not because it was fake. It was true, but it was provocatively true. The people doing it were “life actors” who were going to bring into being a different world through what they did.

(Director’s comments)

The Diggers could be a group of life actors who were acting out things being free, and they would do it expressively so that they were essentially performing what they were doing. That’s why they would be life actors, but the activity was very real.

For example, free food in the park, which became a mainstay of the Diggers’ activity in the Haight-Ashbury—serving food out of a container, a milk can, a large milk can, and serving it to people in bowls that they brought. That food was acquired every morning by women who went to the produce market and got the food that was left over from the day before—mainly women did this. And the food was then prepared, brought to the park.

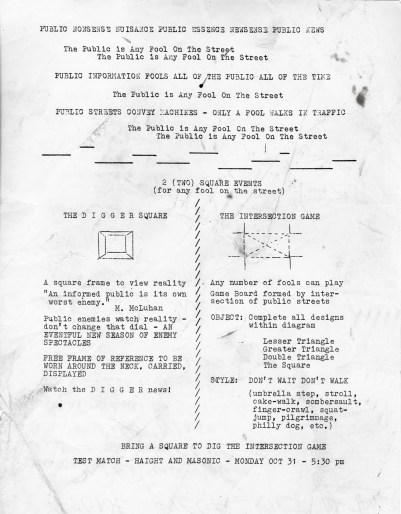

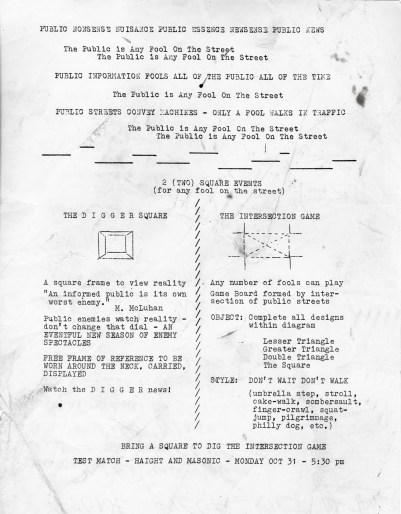

But because it was also theater, we put an enormous frame around the people eating. And it was orange, so nobody could miss it. It was 12 feet by 12 feet of frame, and we called it “The Free Frame of Reference.” And we put it there because John Cage had said, “If you put a frame around anything, it’s art.” So (chuckles) we were looking for the people driving by going to work in the morning who would see people gathered in the park eating food, free, out of a frame, with the panhandle [park] trees as a background. And that this would provoke them, provoke their idea of what they were doing, by going to work. And in the evening when they came back, they would see the same scene. At any rate, with that in mind the Diggers set out to create a whole—cosmology.

Interviewer: I have a question about “The Frame of Reference.” So it was more for the person driving by than the people [who had] to walk through the frame and reframe their point of view?

Peter Berg: No, we did that at The Death of Hippie. We used these frames at The Death of Hippie celebration and had people jump through a frame there to break the plane of reality. But the frame was for the benefit of the people going by. And we just tacked it on to the event of free food. So we were giving people free food, but contrary to the idea that we were quote “hippie Robin Hoods” unquote, it was also a provocative act.

We were trying to influence people to see what was happening as an alternative to the way they were living. There were people that began free stores—I had a free store named Trip Without a Ticket, and the purpose of that was not just to give away things that we would find in front of the door in the morning that were donated to the Diggers, but to enlist people to be managers, to be quote “salespeople” of free goods. There was a room that was filled with mirrors allegedly a changing room but actually a very romantic spot in the free store.

We did events in the street that to outsiders looked at first as though it was a spontaneous event but [which had] a rough script. I remember that late 1966 and the first part of 1967 we must have done at least five of these. One was called The Intersection Game. We passed out pieces of paper that said that intersections should be used for more than just crosswalks; they were actually wonderful places to play games where you could score points by going in different directions and accomplishing different routes in the intersection.

And in the middle of that, we put giant puppets. Like people had these pieces of paper in their hand, and then the giant puppets came out and began talking to each other about who was “in” and who was “out.” One of the puppets was named In, and one was named Out. And in the course of it, In becomes Out, and Out becomes In. And the puppets began walking in the intersection, and of course all this was to stop traffic. And we were very successful at stopping traffic with that.

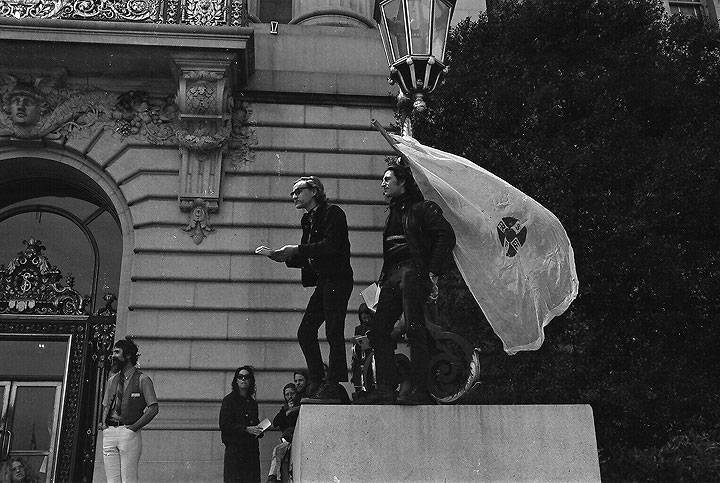

Maybe 1000 people gathered around the intersection to watch these puppets and do this strange game, and the police came and arrested us all [the Diggers]. There was a trial, and when we were released from the trial—we got off, the charges were dropped. They were trumped-up charges. (One of them said that the puppets were lethal. One of the police said that.) At any rate, when we were released a photograph was made of people on City Hall’s steps being defiant, and that photo was on the front page of the Chronicle. It became an emblematic or actually totemic photo for what was going on in the Haight-Ashbury.

Interviewer: I’ve seen that photo.

Peter Berg: Mm-hmm.

Interviewer: Emblematic how? How did it become emblematic?

Peter Berg: Well, because people are being released from jail but instead of just smiling, we were making grotesque shapes and showing ourselves to be defiant about what had happened to us—be expressive about it. And that was really the theme of The Diggers. The Diggers…always had a theatrical motive to enlist the audience in what was going on as well as to accomplish benevolent acts.

Interviewer: What was behind the actions, the theatrics of it, not just the benevolent part but to get people to witness something? Even the stopping traffic. So if you stop traffic, what was in it for the stop-traffic people? What was your theory behind how that was going to change people’s awareness of anything?

Peter Berg: When people look back at the 60s as flower power or with someone making a “V” for victory sign and covered with buttons, that isn’t necessarily the mentality of the people at the time. There were people that had a very strong vision of what they were doing and why they were doing it. This is true in music. It was true in literature, and it was true with the Diggers. We saw hundreds of thousands of people coming to the Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco as being an opportunity to reach a tremendous public and that the people wouldn’t stay there. They would go back. They would go to other places, and anything they shared there [in the Haight-Ashbury] together—whatever their motive was for coming, something would happen to them. They would experience something, and they would take it with them. And we wanted part of that experience to be the idea of transforming society. So to a certain extent and certainly with me, the Diggers were strategic.

It was a strategy, a strategy to involve people in actions and deeds that would make them agents of transformation of society.

I’d come from a progressive theater background. We were trying to influence our audiences. For the Haight-Ashbury, there were going to be hundreds of thousands of people who were going to be engaging in various activities. If those activities were free and doing your own thing, they would carry that spirit with them, and we saw it as a consciousness-raising episode.

We didn’t expect it to go on forever. That’s another reason why it was linked to theater. No one really thought it would go as long as it went. We didn’t really think the city would allow the Haight-Ashbury to continue as the outlaw neighborhood it had become, and the city stopped it. I don’t know if most people are aware, but it wasn’t boredom that killed the Haight-Ashbury. The city actually made Haight Street one-way, installed yellow mercury vapor lights, like a prison camp, and patrolled it every 10 or 15 minutes with paddy wagons to pick up people or harass people on the sidewalk.

So it became a very grim place, at night especially. By late 1968, it had become very grim, but it was part of a city program to make it that way.

Interviewer: You’re in a really good position to take us on sort of the journey from late ’66 to late ’67. Going back to the point at which LSD was illegalized and there was a Love Pageant Rally that was organized. Do you have memories of that?

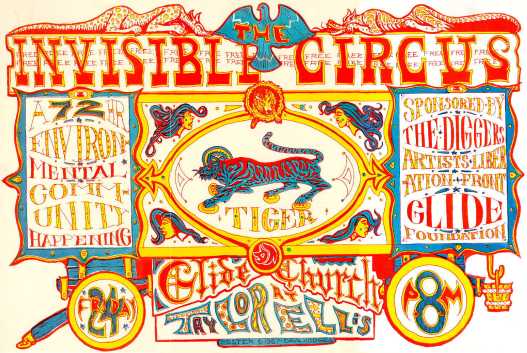

Peter Berg: We weren’t friendly to that event. We thought that it featured too many stars, that it was making star personalities out of people and that it was not carrying out the highest intentions that we could imagine for the population that was gathered in the Haight-Ashbury. Our reaction wasn’t favorable. We held a counter-event called The Invisible Circus that was much more like what The Diggers envisioned for the future.

Interviewer: Let me back up for one second. I do want to get into The Invisible Circus. What you’re talking about now that you weren’t in agreement, was that around the Be-In or the Love Pageant Rally?

Interviewer: Yeah, I think you’re mistaking—

Interviewer: The Love Pageant Rally was—I think the Oracle was involved, and they were sort of saying that the illegalization of LSD that happened on October 6, 1966, shouldn’t have happened. We should have a right to take LSD, and there was a celebration that preceded the Be-In. The Be-In happened in January of ’67.

Peter Berg: I did confuse them.

Interviewer: Just to back up, do you have any recollection of the Love Pageant Rally itself?

Peter Berg: Diggers weren’t involved in it.

Interviewer: As far as I’m understanding from the history, before the Be-In, The Diggers did have a Death of Money event.

Peter Berg: Right.

Interviewer: Can you talk about The Death of Money?

Peter Berg: There was an event the Diggers staged in late 1966. It was titled The Birth of Haight and The Death of Money. It was one of those pageant-style theatricals that we did in the street. I had a lot to do with it because I set up the elements for it, but people who became involved with it as it was going on, from their point of view, it was simply a spontaneous happening. And one of the features was to have an enormous coffin.

We had people dressed in animal heads who were wearing black gowns, and they took money, huge pieces of money—stage money—and put them in and out of this coffin in a march down the street, Haight Street, singing, “Get out my life, why don’t you, babe?” to Chopin’s “Death March.” And it went, “Get out my life, why don’t you, babe?” (Sings the line in a slow drawnout manner & then laughs.) [Note: Lyrics from You Keep Me Hangin On, Diana Ross]

And there were thousands of people that watched this from rooftops and windows. We also handed out pennywhistles, and people blew them. We gave people rearview mirrors that we had gotten in a junkyard, and they reflected the sun onto the street. You saw light bouncing around. Really a marvelous event.

Interviewer: Some of the philosophical or political underpinnings of that around money and the Diggers’ whole relation to money and what you wanted people to understand about money—talk to us a little bit about that.

Peter Berg: The background of the 60s is in the midst of two major historical trends. One is that people felt repressed. Gays felt repressed. People that used marijuana felt repressed. People that wanted to use actual language felt repressed from using what were called “dirty words.” There was personal repression that touched just about everybody, and on the other hand there were two social systems that people were being asked to choose between: capitalism and communism.

And the two actually are very much alike when it comes to the way they treat nature. They’re both industrial-age oriented philosophies, and there are people that simply didn’t want to play those games. They didn’t want to be repressed. They didn’t want to repress people. They didn’t want to be at war, and they didn’t want to engage in materialistic society—and they were pro-nature.

Think of [the] typical vision of a hippie as barefoot, that’s touching grass; long hair, meaning not cutting your hair; organic food first was introduced during the 60s; natural childbirth. All these things very naturally oriented. People wanted to identify with nature. They wanted to identify with joy rather than these choices they were given about ideologies or about repression.

So in the midst of that, we thought that society could move toward a more liberated—much more liberated—freer sort of existence, and we wanted to push that rather than to simply oppose the war or oppose American society. It was pro-active as far as the human spirit.

Did that answer what you asked me?

Interviewer: No, but it’s fine. It sort of did.

Peter Berg: Oh.

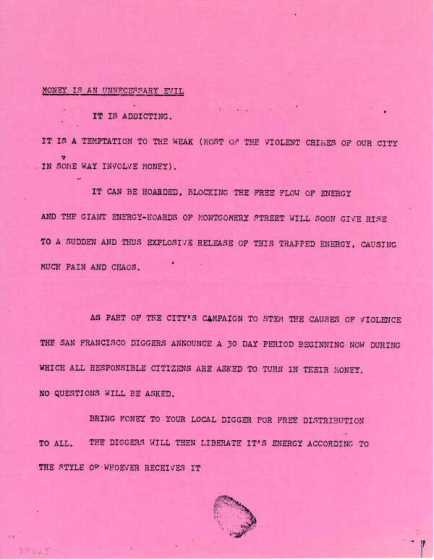

Interviewer: I mean, I was linking it back to The Death of Money event and actually money itself as something that you were telling people to put in a coffin, that was carried with animal-head masks. What was that about?

Peter Berg: Well, money—cash money is symbolic of materialistic society, and to do things that weren’t based on cash, weren’t based on making money in order to gain your social ends or personal ends needed models. We needed to provide models. So we renounced money, and we counter-posed it with free events. Free food, a free place to stay, the first free medical clinic was ours, a free store. There was even someone that walked around with currency—a $100 bill in his hatband—who called himself The Free Banker, who would give money to people who asked for it. And then go to other people and say, “Give me $100. I need to renew my hatband.”

We had a poster. It was the 1% Free poster. Toward the fall, I think, of 1967 [ed. correction 1966] I made a poster of two Tong men, Chinese Tong men, leaning against a wall, and at the bottom it said, “1% Free.” It was very provocative poster. Storekeepers thought we were extorting 1% of the money they made. I walked in the stores, gave it to a storekeeper on Haight Street and they’d say, “What does this mean? I’m supposed to give you 1% of my money?” But they said that. I didn’t say it. We put them on banks. We put them on stanchions of the freeway. We put them on walls everywhere—”1% Free”—to provoke people to think about what is 1% Free? Am I part of the 1%? Should 1% of everything I do be free? People responded to it that way.

Interviewer: If you could again give the explanation of what you meant by “1% Free,” that’d be great.

Peter Berg: From the beginning?

Interviewer: No, just towards the end.

Interviewer: After what the store owners were saying. As opposed to that, what you meant was . . .

Interviewer: Were people asking you, “[My] 1 % ?” —

Peter Berg: We made several hundred of these. They were about the size of a human being, and we made them on newsprint. And I brought them into stores and gave them to store owners, and the store owners would think that we wanted to extort 1% of their money. And they would say, “Am I supposed to give you 1% of everything I make here?” And other people thought it meant that only 1% of the population could live free.

It was meant to be provocative. It was rather than being the kind of poster that tells you what to do, it was the kind of poster that was more theatrical to cause you to think about what could be 1% Free.

Interviewer: So you didn’t have your own belief behind what that “1% Free” meant? It was total provocation, or was there somewhere in there a right answer?

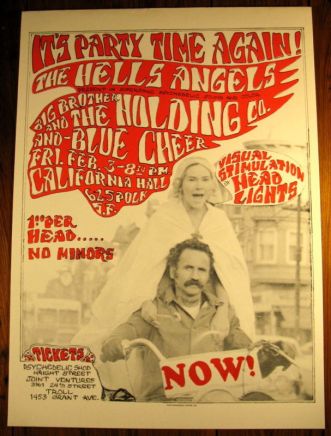

Peter Berg: The 1% came from the Hell’s Angels. The Hell’s Angels wear a patch that says ‘1%.’ It’s because a writer writing about them once said, “Only 1% of the motorcycle riders are like that. Are outlaw bikers.” So the Hell’s Angels took that as emblematic, that they were that 1%. So I suppose part of it was that at that time 1% of people were behaving as though they were living in a free world—free economically, free spiritually, free creatively.

We used to tell people put “free” in front of any word that you’re fond of and start doing it. So if you liked to cook, become a free cook. If you liked to bicycle, become a free bicyclist. If you want to be a entertainer, be a free entertainer. In fact, we brought the Grateful Dead to the panhandle to give a free concert for the first time. The first free concert in the park was The Diggers getting a truck and bringing it to the house of the Grateful Dead, putting them on it, and driving it to the park and them playing.

Interviewer: Some people have criticized the concept of telling people, “Yeah, everything is free.” Well, “Yeah right. How do you live if everything is free?” I’m sure you heard that criticism then and since. How do you respond to it?

Peter Berg: The criticism that it’s unrealistic to act as though everything is free is taken from a historical perspective. It’s a perspective that doesn’t think in terms of process. For me, the free was not ideology. It was for a process, and that was to liberate people. Take a group of people who were just coming out of high school or college. Should they work for a living, or should they start thinking of communal ways to get what they need in order to live a more free life, a less materialistic life? A life that’s more personally creative.

We were offering the alternative of what does it look like if you do that? And we did not believe that we had a license on it. We weren’t franchising being free. We were offering the stage for people to be free upon, for them to be on the stage and act it out. Now, what’s going to happen from that? Well, when you have a process, it’s a process, and you go from one point to the next. I really didn’t know where it was going.

I knew that we were part of anarchist history. I knew that we were part of the great progressive liberatory historical movement and body of thought, and that, I think, was a real accomplishment. It’s difficult to become part of that body of thought.

Interviewer: When you first started hatching these ideas and the whole “life theater” concept, did you have in mind that it was going to grow so exponentially in terms of the numbers of kids who were going to be arriving in the Haight-Ashbury?

Peter Berg: The Diggers had a better idea of how many people would come to the Haight-Ashbury because we were actually living that life, and we saw how incredibly effective it was.

The influence of early psychedelic rock music was tremendous. The influence of individuals who were songwriters at the time—there must have been six or at least a half dozen songs saying, “Go to San Francisco. Wear flowers in your hair. Tell the police to cool it. And find out who you are.” They were the top 10 songs in the country. So we were in a position to know how people were reacting to that.

We’re the ones that had done a benefit when there had only been an audience of, say, 150 or 200 people for the play that had gotten busted in the park. We were the people that saw 5000 people show up at the benefit. Where did they come from? Who was this group of people that were remnants of the left and from the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war protest who are also smoking marijuana and living communally in the Haight-Ashbury? This is a whole new population. We had seen it, with that exponential growth. We were a part of it, and we knew that we could stimulate it.

We told the city that there would be half a million or a million people here, early in 1967, and the reaction of the mayor was to tell people not to come to San Francisco. We were saying, “Look, they’re going to be here. Provide the means for them to be peaceful.” They’re making a pilgrimage to—I think I told Herb Caen that it was a “sacred city”, that San Francisco was sacred. (laughs) People were coming here for spiritual reasons. At any rate they were coming, and they weren’t from northern California, by and large. They were from all over the United States.

Interviewer: How were you receiving the fact that the city was not going to support this influx of kids and that they were coming?

Peter Berg: Our reaction to the city refusing to take a positive look at this phenomenon was to decide that the Haight-Ashbury was our city. It was as though there was a wall around the Haight-Ashbury. The city police actually developed a special squad to infiltrate and find out what was going on because they didn’t know what was happening there. The health department created a subgroup just to investigate apartments in the Haight-Ashbury—that were communal apartments—for health violations. I mean, the neighborhood was out of control. We could stop traffic whenever we wanted, and we did several times. We had events in the park without permits. We could do anything we wanted in the panhandle. We even had large events in Golden Gate Park. Some of them had permits, but Digger events never had permits. We could take over storefronts and make free stores out of them. We could turn apartments into free communal apartments. We could serve food in the park if we wanted to. It was our neighborhood.

Interviewer: We’ve talked to a number of people, one after the other, who say, “Yeah, well, I got here and just went to a Digger apartment,” or, “I got Digger food.” You were definitely serving that community. You were the infrastructure in many ways.

Peter Berg: When the city decided to counterattack and make the street one-way and put patrol cars and paddy wagons [on the street] every 15 minutes, our strategy was to go to City Hall’s steps. And one of our theater events was called Free City, and Diggers showed up every morning on City Hall’s steps, giving out free food, reading poetry, delivering manifestos. Really an amazing three months. It was in 1968 when things were winding down. We thought, “Well, if they’re going to take our neighborhood, we’ll take their city.” (laughs) We went to City Hall’s steps.

Photo © Chuck Gould

Interviewer: [Was] that principle that was guiding…[you] true of your thoughts for 1967 as well? I mean, you did that in 1968, but might it as well have happened in 1967? Going to City Hall and having that kind of an action in City Hall?

Peter Berg: Mm-hmm.[affirmative] Things like that did happen. They happened in other neighborhoods. For example we supported the idea of a black free store in the Fillmore. I think it was called Black Man’s Free Store. We brought free food to the Black Panthers in Oakland and suggested that they start giving free food away, and that is where the free breakfast program came from. I was with that group. They were stunned that we brought food to them. Bobby Seale—I remember we brought rex sole, the fish, and he looked at it and said, “Man, what is that ugly looking fish?” We said, “It’s sole, you know. It’s rex sole.” It’s the first time he had ever seen the actual fish.

Interviewer: You remind me of something I wanted to get back to. When you were talking about Emmett Grogan looking down from a rooftop on the riots in the black community and his thought process that actually led to some of the Digger philosophy—I think there was some piece of it that I didn’t totally understand that led to the sign on the Mime Troupe door or that manifesto of the 10 points or whatever it was critiquing the Mime Troupe. I’m not quite sure the link-up between what Emmett was perceiving going on in the black community with the riots and being a white person in a white community.

Peter Berg: The idea of The Diggers was stimulated by the riots in the Fillmore of African-American activists and outraged people. In the sense that those riots were an acting-out of militant feeling and need for social change. Other than the anti-war movement, there wasn’t a similar acting-out for people who were not involved on the other end of that racial divide. If people in the mainstream acted out how they wanted to be or acted out their rage against repression and against materialism and against the failed ideologies of both capitalism and communism, how would they do it?

They would do it rather than burning a building, they would convert a building to make it free. Rather than setting a police car on fire, they would provide an event in the park that would let people see what a new person could be. So it made sense to defy the left and its formula for change, and to throw out a new image of change as a much more advanced idea of social mutualism. And that’s what eventually took place. I think the original thought was of rage of a person in mainstream society against the society would take a different form than rioting. You would take a more proactive form, and that was the seed for the—Everything Is Free; Do Your Own Thing—that eventually developed.

Interviewer: Talk about ‘Do Your Own Thing.’ That phrase was coined then, I think by you, and it became like a household phrase. Talk about ‘Do Your Own Thing’ and using that phrase and where it came from for you and what it was intended to mean for people.

Peter Berg: ‘Everything Is free’ was aimed at materialism. ‘Do Your Own Thing’ is aimed at the repression that we felt people were suffering under about their own creativity. An example: I knew a woman that was introduced to making fabric and dying it in a way that was used in India, and she was fascinated by it. It was called ‘tie-dying.’ At the time, I had not seen any tie-dying. Only her, and she was a teacher of fabric design. We encouraged her to do it at the free store, show people how to do it because it was so personally creative. The knots that you made, the dye that you put the fabric in—would be your own.

Eventually she started teaching classes and as free classes at the Straight Theater. I’ve seen as many as 50 or 100 people with pots of dye learning how to do this, as a liberating expressive practice. Well, pretty soon all the white shirts that we were being given at the free store by people that dropped out of the business world and left their white shirts for us—nobody wanted these white office shirts. So everybody tie-dyed them. Well, that’s where the phenomenon of tie-dyed material and its influence on that culture, the Haight-Ashbury culture, came from. That was an example of ‘Do Your Own Thing.’ She wanted to share this with other people, and she used The Diggers as a medium to do that.

Interviewer: You’ve talked a lot at times about the role of the imagination, freeing the imagination, and acting as if basically if you can imagine it into being, then it can manifest.

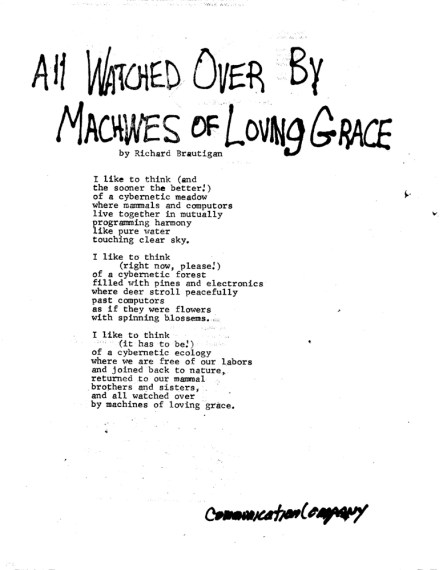

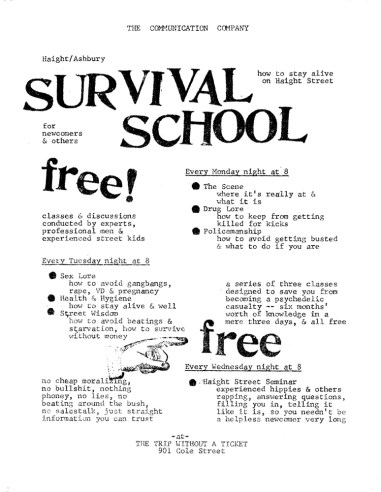

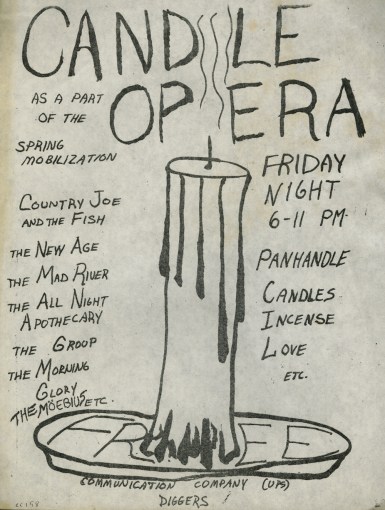

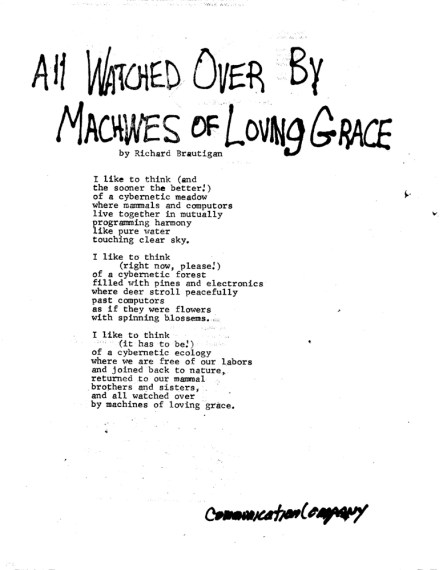

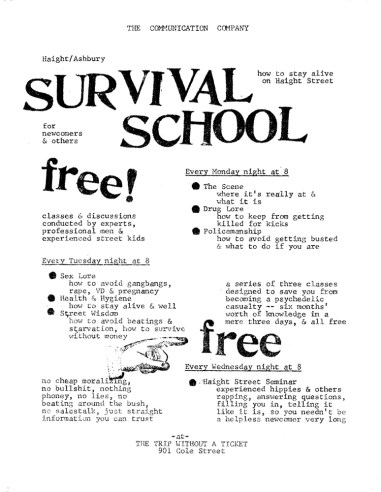

Peter Berg: The Diggers had a street publishing company that was called the Communications Company. I helped get the machines that the Communications Company people used. The idea of the Communications Company was that if something happened, you could have information about it on a sheet of paper on Haight Street in a matter of minutes. I think the longest it ever took to get something out was half a day, and the fastest was one time I walked in with something, asked them to print it. They printed it, and I just walked out with it, and started distributing it on the street. They were “free street sheets.”

Anybody could write one of these. We were seeing them all the time. We had no idea who was writing them. Some of them were really memorable. I remember the one when Martin Luther King was killed. A sheet came out that said, “Goodbye, Brother Martin. Today is the first day in the rest of your life.” It’s the first time I had seen that phrase. I think it’s a line from Gregory Corso, the Beat poet, by the way. At any rate, the Communications Company was self-consciously making itself a means for people to print anything they wanted to print. Richard Brautigan’s poems, many of them came out first as “street sheets.”

Not only known poets, but people that were writing poems for the first time. Information about where to get things. Where to get things that you needed. Where do you get a place to stay? Where do you get free food? were on these sheets. So that was an example of ‘Do Your Own Thing’ and the means to do it.

The free store was like that. We had soldiers in uniform come into the free store, take off their clothes, pull clothes from the rack, and leave their uniforms behind. I mean, they left the Army in the free store. They used it as a place to undergo a personal transformation.

Interviewer: You sure witnessed a lot of that personal transformation going on because that’s so much of what the scene was about. Going back to the Be-In, which you started to talk about before—talk some about the Be-In and why you weren’t involved in it and what you perceived it doing or not doing.

Peter Berg: The Haight-Ashbury was divided by two forces—at least two forces. One of them was The Digger phenomena that I’ve been describing, and the other was the Haight-Ashbury merchants. The Haight-Ashbury merchants for The Diggers represented capitalism. They were taking advantage of the situation. If hundreds of thousands of people were coming, they would sell them the beads that they wanted. We were the people that were providing their consciousness with ideas. The merchants were selling things.

So this division sometimes took the form of overt proclamations. The H.I.P. [Haight Independent Proprietors] merchants saying that they didn’t want to have anything to do with the other elements in the community or divorcing themselves from things that had been done. But they were also promoting things that they wanted to do, and the Oracle newspaper was identified with the H.I.P. merchants.

And the idea to have a Human Be-In was carried by groups like the Oracle and other groups. The title, of course, came from Allen Ginsberg, and the participants were all kinds of people, including Gary Snyder and Lenore Kandel, poets identified with the Beat generation. And then later with nature. But those poets were treated as stars at an event that we felt was tainted by commercial[ism] and cult of personality.

So our feeling about it was that it should be changed from the original prescription to a different kind of event. And for that purpose, Emmett and myself met with Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder and talked about our ideas as opposed to what we thought were the merchants’ ideas, and a lot of interesting things came out of that meeting. One of them was the we decided to provide free food at the Human Be-In, and somewhere along the line one of the major producers of LSD put something like 5000 tablets in our hands to distribute at the Human Be-In. So the way we related to it in the end was to serve food and give people LSD.

Interviewer: Your feelings about LSD at the time?

Peter Berg: Excuse me?

Interviewer: Your feelings about LSD? What was its role in creating this new vision for people or the role of the drug, period?

Peter Berg: Hallucinogenic drugs like LSD give people an opportunity to dissociate what from what they consider to be normalcy or the reality that they’re asked to participate with. I always saw LSD as being liberatory, as having the capacity to change someone’s perception and invite new ideas in. Not necessarily coherent ideas, but even the idea that your mental stream can be interrupted is instructive. I know my own experience is that having taken hallucinogenic drugs, I’m much more available to new ideas or things people say that are unexpected. The unexpected becomes more normal, more the expected.

The unexpected becomes expected, and I think that’s a very creative state to be in. It certainly is helpful when you’re trying to get loose from as constricted a society as the United States had become and was becoming in the middle 60s.

Interviewer: You’re talking about the split between the Oracle and, say, some of the Digger philosophy. I think I’ve heard you say or read a description of that as the Oracle being more of that “change yourself from the inside, and all things will change,” and that you guys were more saying, “Change your external reality, and then you can change society and all will change.” Can you speak to that dichotomy, if in fact there was one? Or the subtleties of that?

Peter Berg: Anybody that was around in the 60s was being influenced simultaneously by everything from political to personal to social challenges. Politically, the war in Vietnam; Socially, Civil Rights, repression of black America; and personally, from being—I believe—creative, being expressive.

Normalcy pushed very hard. An example would be if you had a mental breakdown and went to a public institution, you would be treated by someone whose goal was to make you a tax-paying employed normal citizen rather than being a free, creative human being—at least from my point of view. And I think that was a carryover from the 1950s when … [a] kind of a normalcy cult had taken over the United States.

[Abrupt end of recorded material DVD disk 1]

[Beginning of recorded material disk 2]

Interviewer: OK. Any time Peter.

Peter Berg: Spirituality of a different kind… was considered normal during that era, associated with Buddhism or with a sense of transcending, transcendental consciousness, was one of the influences everybody felt in one form or another. And the desire for social change was one of the influences everyone felt. It would be harder to produce social change than it would be to change one’s consciousness in terms of spirituality, I believe. And the real challenge would be to introduce people to a variation—a social variation from what they were experiencing day to day.

So for me the real challenge was to have people introduced to a social alternative not just—not just a personal alternative.

Male Voice: For me the real challenge…

Peter Berg: So for me the real challenge was to introduce people to a social alternative. There were plenty of spiritual alternatives and you could do that on your own time, while you’re interacting with other people. The social context was more important to me.

Interviewer: You said some of the same things, but I really thought that phrase – to break out of a normalcy—the repressed normalcy of the 50s or however you put it—but you put it back into the 50s context essentially because that’s important for us to remember— just that short phrase.

Peter Berg: The 1950s were extraordinarily repressive. There was of course repression of the lefts during the 50s, but there was also an eagerness to appear to be normal, to engage in quote the “American Way of Life”, to act it out. And if you didn’t do this, you were repressed or you were thought to be interfering with the proper operation of society, which Lenny Bruce epitomized in his humor.

During the 50s, I remember the power of things like Elvis Presley or hearing black rock music for the first time—how strong that was as a clarion, a summons, to a different kind of identity—much more sexual, much more expressive, much more liberated.

And, I think that’s where the Beat generation came from—the desire to have a more liberated identity. And by the 60s, they were the children of the Beats; they were the people that were going to carry it forward as far as they could.

Interviewer: I think a lot of people used the phrase saying, “wherever I was before I got to San Francisco I felt like a misfit or I was told I was a misfit or I didn’t fit in until I got to the Haight.”

Peter Berg: I think everybody was told they were misfits. It was kind of a policing of society where everyone was under the influence of this extreme cult of normalcy.

Interviewer: I want you to talk about ‘now’—the concept of ‘now’ and being here ‘now’. In the moment of the 60s ‘now’ became sort of a cry of The Diggers, right?

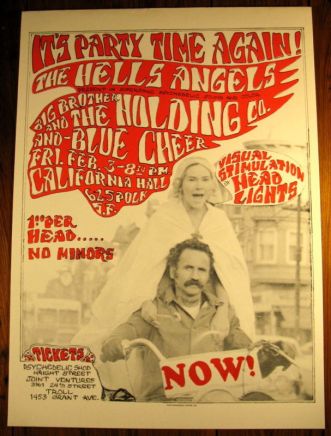

Peter Berg: The word ‘now’ pops up in Digger events. I remember printing up pieces of paper that just had the word ‘now’ with an exclamation point and giving it out to people during one of our events. There’s a photograph of a woman riding on the back of a motorcycle holding one of these signs up. The motorcycle’s going down a street crowded with people on both sides all cheering.

Why? Because sensibility was: what could be accomplished in the moment, at the moment, had transformative power that preconceptions of what could happen or a plan did not have. And we were eager to allow that to occur, to allow ‘now’ to happen.

We made a film in 1968 titled Nowsreal, N-O-W-S-R-E-A-L, and the whole philosophy is in that title. Part of it [making the film] was to go to a television station and to film the reaction of the people in the television station to us making film of them making television or carrying out the business of television.

And we staged an event in front of the television station, went into the lobby, stopped people on the street, showed our own video of people burning money, and people at a Free City Convention that we had televised. We were showing free T.V. to the T.V. studio. And the police came to this event. They were summoned by the television channel. (chuckles) These things were incredible. When I recall the élan—how happy they made us feel to do them—it was incredible.

Anyway, someone stood with a sign saying NOWSREAL. We showed the video of people burning money. Television executives came and looked at what we were doing (laughs). They called the police, the police looked at what we were doing. The police began asking the television people, “Why are you disturbed by this?” It was an amazing event.

Interviewer: That famous photo of the motorcycle with the woman holding the ‘Now’ sign, if I’m not mistaken, that was also linked to the arrest of the guy driving the motorcycle, Chocolate George?

Peter Berg: The woman that was holding the ‘Now’ sign and was riding on the back of the motorcycle was part of a demonstration that took place at the end of one of our free street events. And the police arrested a couple of Hell’s Angels. And a group of people were gathered in the streets—several thousand people— marched to the police station that was nearby in Golden Gate Park and protested his arrest, and passed around a hat, and raised the money for his bail, and we got him out of jail.

Interviewer: What was the relationship between The Diggers and the Hell’s Angels?

Peter Berg: In the middle 60s, the kinds of groups that were opposing American society were hopeful that they could become political mainstream. The old left/ the new left were really aimed at putting candidates in office who would be elected representatives, or causing legislation to be passed.

The groups of people who were capable of armed rebellion against the United States government, and which would be necessary if the government continued the course that it was on which was pro-Vietnam war, not providing enough relief for civil rights, repression of individuals, repression of the counterculture. If that continued, there would need to be people that were able to actually fight.

All over the world there are groups who were combative and take that form of address to deal with their social problems. In our time, in 1967, these groups were the Black Panthers, who were armed. And the groups who were willing to fight were groups like motorcycle gangs—people that were capable of fighting.

But from my point of view The Diggers were offering such a radical extreme to American society that we should be identifying with the groups who express themselves more radically in terms of physical violence. I identify with the Black Panthers, and the first time we put out a collection of The Digger Papers, the Black Panthers were advertised on the back cover of the magazine. And we thought of the Hell’s Angels in the same way. And strangely some of the Hell’s Angels thought of us as being a kind of strategic ally.

I remember we staged an event that was called The Free City Convention. At this event, by the way, our idea of a convention was to have people holding signs and signs hanging from the air that said, “Free Expression” , “Free Frame of Reference”, “Free this”, “Free that”, and people burning money—is what happened at this convention.

But before it—the Hell’s Angels were participants—and before we began, the police showed up at the Carousel Ballroom where this event was going to be held and said, “Wasn’t there a way that we could all get along better together?” And the Hell’s Angels’ President of the San Francisco chapter took me aside and said, “What should we do? How should we relate to this?” And I told him that it would not be in their best interest to become allies of the police department. That there would be a ringer in it somewhere and to avoid it—not to make a deal with them. That it wasn’t necessary. At any rate, it was very strange to be consulted about strategy by an outlaw motorcycle gang. But apparently they thought of us in a way, not similar to, but as sort of a partnership.

Interviewer: This might not be fair to ask but some of the use of non-psychedelic drugs that appeared in the scene—that you understand there were a number of Diggers who were using drugs like heroin and a number of Hell’s Angels who were bringing hard drugs into the community. Talk a little bit about hard drugs, Digger philosophy and the role of the Hell’s Angels.

Peter Berg: I wish I had your questions in here sometimes, by the way. It would be very nice to have you asking that so that I could say to you, you know, why are we headed here.

Interviewer: Why are we heading with this specific question?

Peter Berg: Yeah.

Interviewer: Well you can ask me that, and then we could figure out a way for me to rephrase it. I’m not headed anywhere…

Peter Berg: Well, I have to begin by saying, “The use of hard drugs…

Interviewer: Don’t worry about that. If that’s inhibiting you, don’t worry about it. If it’s not flowing easily, we can add it back in when you’re done talking about whatever it is and just put a tagline in and we’ll cut it in. So I don’t want you to have to stop your thoughts to think too hard about incorporating the question into the answer. And I can try to make the questions simpler. The role of hard drugs for The Diggers.

Peter Berg: My experience with drugs began when I was 16 and I took some diet pills. They were Dexedrine, and they were extremely strong amphetamines. The next drug that I took personally was in college and I ordered peyote from the Texas Cactus Company, and we ground up peyote in a meat grinder, strained it through cheesecloth and drank it in shots and (laughs) became hallucinatory for three days. I’ve used all kinds of drugs and for all kinds of reasons.

The role of hard drugs in affecting the counterculture and in quote “ruining the Haight-Ashbury “ unquote has, from my point of view, always been overstated. The police presence would be much more of a factor. The fact that so many arrests were taking place and so many infiltrations had occurred. I’m not trying to make an excuse for non-psychedelic drugs, but seeing them as being painkillers isn’t a bad way to view them, considering what was happening to people I knew in San Francisco at that time.

Interviewer: But they weren’t being pushed in some way as sort of a money-maker —not by The Diggers but by others—the Hell’s Angels for example? Were they bringing drugs in just to deal them?

Peter Berg: I didn’t have any personal experiences with people that were wholesaling drugs.

Interviewer: We were talking about the police; do you remember any of the police in particular that you might have had personal interactions with?

Male Voice: Before we get into that, Peter, could you talk to the fact of how important LSD was in general to the counterculture? Could you conceive the counterculture movement without psychedelic drugs?

Peter Berg: I can’t imagine the music or the art or the poetry of the 60s without LSD. I think it was indispensable for people to arrive at a more liberated consciousness. Whether or not people should keep using LSD is an entirely different question, but at least initial experiences with it were so liberatory I can’t imagine it without them.

In one of the essays I wrote for The Diggers, I said that ‘everything is free and do your own thing’ is social acid, meaning that it had the impact on social events that LSD had on an individual mind. So the Diggers in a way were LSD, but it was social LSD.

Interviewer: That’s a pretty wonderful image and I think it says a lot about the deprogramming or deschooling aspect of LSD in changing your whole thought pattern. I know you talked about it in terms of the Digger philosophy of imagining and using your imagination and acting as [if], “We’ve won the revolution.” So if there’s any more that you want to add to that, even this concept of ‘we’ve won so act as if’ and this LSD acting out through Digger philosophy and Digger actions…

Peter Berg: I set up an event at the Straight Theater and it was called The End of the War. The image for the poster was a Ho Chi Minh with his arms around Lyndon Johnson and crossed American/Vietnamese flags. And the purpose of that event was to portray the kind of consciousness that might exist if the war ended and to presuppose that the war was over.

And we did a number of things that were (laughs) incredible at that event. There was a naked dance performance. There were cargo nets hung along the walls for people to climb up and down the walls. There were branches of trees and palm fronds for people to parade around with. There were two different rock groups who were interspersing their music. There was a film made of volcanoes erupting, tidal waves coming, hurricanes blowing, seeds sprouting, nebula exploding to give an idea of connection with nature. It wasn’t entirely scripted, but it had the kinds of elements that we thought would prevail or could prevail with the war over. So for our purposes, we ended the war.

Interviewer: How was that perceived by the participants at the time?

Peter Berg: The people that were involved with this event included The Living Theater who came en masse to perform Paradise Now, which was a play of theirs. They’re a New York-based theater group. They were visiting San Francisco to see what psychedelic culture was going on here, and they were ready to perform this. They performed this play in New York wearing G-strings and saying, “I can’t be naked”, that they “wanted Paradise Now” “I want to be naked” “I can’t smoke marijuana.” Anyway, they sat in the balcony of the theater watching this event saying that everything that they would have done was completely inappropriate—that people were smoking marijuana, (laughs) people were being naked, people were acting out quote “Paradise Now” unquote. So that’s always stayed in my mind as a reaction to this event that we did.

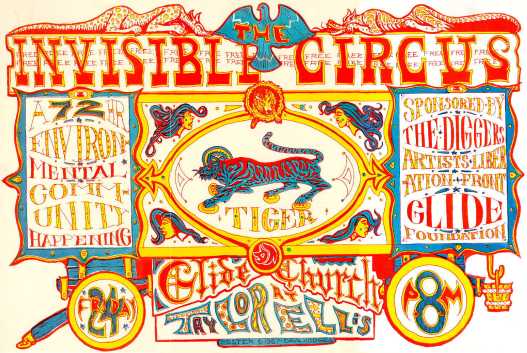

Interviewer: Another event that you had mentioned that we got away from and I cut you off about it was about The Invisible Circus as a response to the Be-In. You said you didn’t agree with the Be-In but you wanted to create something different and your response was The Invisible Circus. What was that?

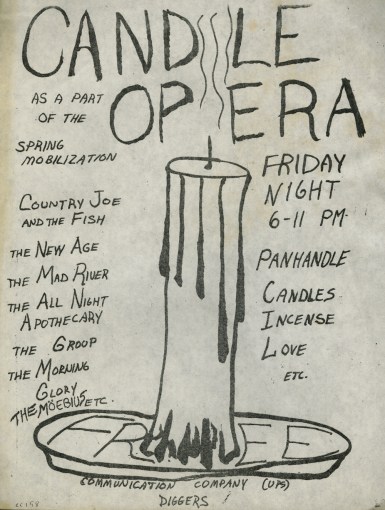

Peter Berg: There was a group named The Artists Liberation Front, and it included some of the really well-known poets and music and theater people in San Francisco in the alternative direction. Lawrence Ferlinghetti was one of them. Michael McClure, Kenneth Rexroth had something to do with The Artist Liberation Front. The San Francisco Mime Troupe had a lot to do with forming this group, and they had started a series of events and had previously used Glide Church as a site for events that were free and were inviting of neighborhood participation—open to the public entirely without any tickets.

So Glide Church was a site that we saw as a potential to use for a very large underground event. So in collaboration with some of the people who were in The Artist Liberation Front, and a number of better-known artists, Lenore Kandel, the poet, Richard Brautigan, another poet, some others, we decided to do an event.

Brautigan named it The Invisible Circus, and at this event we would expose people to alternative kinds of behavior and activity that would be so totally engaging and so participative that it would change their minds about culture in general. In our minds, three days would be a good event.

And we invited groups that were as different as sailors at a Navy base to community groups from the Mission District and Fillmore District, Haight-Ashbury—all kinds of different groups in the city. And at this event, we wanted to create an environment that would be indicative of a liberated city, and it was. It was really incredible.

I designed a couple of different things that I can describe. One was to have an artificial wall made out of paper in a room on which we played footage of the earth from a spacecraft—from a satellite. And in the middle of playing this, a group began playing music behind the paper screen and belly dancers broke through it.

Another event was (laughs) to have a panel on obscenity that had religious figures, lawyers, and while they were discussing obscenity in a glass case that was in the wall behind them that could be accessed from the other room behind the wall, someone took off their clothes. At the same time, a fire-eater began blowing balls of fire (laughs) in one corner of the room. And one of the participants got up and took off their clothes and changed into surgical gloves and mask (laughs) just to completely disorient everyone about what obscenity might be.

Lenore Kandel had a foot-reading booth which was truly for fun but that people began taking seriously. And she had a diagram of a foot as though it was a hand and different parts of the mind (laughs) and how they related to parts of the foot. Everything about it [The Invisible Circus] was made to disorient people. I think Emmett filled up an elevator with shredded plastic so that when you got in the elevator you had to climb up two or three feet of shredded plastic and stand above the floor of the elevator for no reason except to, you know, change your anticipation of what the elevator might be.

There’s a room in it [Glide Church] that was used for getting ready for weddings and we converted it into a place to have a sexual encounter—with candles and oil and I think there was Arabic music playing. Brautigan had an instant press and went around getting [and printing] people’s poems that he called the John Dillinger Computer.

All of this was to subject people to more intense and various forms of disruption of their anticipations, and our anticipations were that it would go on for three days, but the people in charge of Glide Church couldn’t see that (laughs). They stopped it I think after about 8 or 10 hours.

Interviewer: So why had it been called ‘The Invisible Circus’?

Peter Berg: ‘The Invisible Circus’ is that kind of a phrase that is evocative. What is a circus and what is an invisible circus, something that goes on in your mind? or that people are participating—the normal activities of life are actually very heightened and beautiful or interesting, worth looking at twice—they’re a performance?

Interviewer: When did this take place? Do you recall?

Peter Berg: 1967.

Interviewer: But do you know where on the timeline of ‘67?

Peter Berg: Mm, I’m putting it early in the year. February maybe.

Male Voice: I think it was March, but the reason why he was in opposition to the Be-In was because of the participation…

Peter Berg: Oh, that’s right. It would have been March or April, in that frame. [The Invisible Circus is listed as being Feb 24-16,1967 on the diggers.org website.]

Interviewer: So what we’re asking is the significance of it being in opposition to the Be-In or a response to the Be-In.

Peter Berg: The Invisible Circus didn’t have any stars. People walked in the door and these things were going on. They weren’t introduced. They weren’t—there was no MC. It was completely democratic in the sense of assembling what you saw before you. Whatever experience you had would be your unique experience… It makes each member of the audience a performer because they are assembling what occurs in front of them. There’s no order for it. So to give it order you have to become the creative editor of it. That was our idea.

Interviewer: Was the audience or the people who were witnessing this or trying to put it all together expected to start performing their own random actions?

Peter Berg: As a result of this, people began performing their own acts and they were invited to write poems that would be published. They were invited to get on the stage. They were involved with dance and music. So they, the participants, became the performers; that was the idea.

Interviewer: You were perceiving it as in reaction to the Be-In. Was that shared by others that the Be-In needed to be deconstructed in some way and that you needed to have this kind of event or was it for many people just another event in this trajectory that was building toward the summer [unintelligible]?

Male Voice: I think it’s important [unintelligible].

Peter Berg: Sure.

Male Voice: Okay, we are clear.

Peter Berg: The Be-In was constructed as a central stage event, uh…Start over again?

Interviewer: Very good, excellent.

Peter Berg: The Be-In was constructed as a central stage event which is hierarchal —means that there are star entertainers or star philosophers or star speakers who everyone else is supposed to listen to. The Digger idea was that everybody could be a presenter, an expressive person and much more democratized view of what an audience was.

An audience was all potential performers. So our reaction to the Be-In was reaction to a center stage with stars arrayed on it. And I believe that the people that were on the stage had a revelation that day looking at what was in front of them. For example, the event began with a parachutist landing in the middle of the field—landing in the middle of the group of people. And people persisted in their own behavior the way they do at rock concerts now but was unusual then.

Interviewer: Yeah. I thought I read that the Be-In itself was an effort to bring the New Left and the emergent counterculture together. You’ve made it sound like it was formed by the Haight Independent Proprietors or merchants and I’m a little bit confused by that.

Peter Berg: I don’t even remember anyone on the stage at the Human Be-In that represented progressive ideas that was a representative of the anti-war or Civil Rights Movement. So what you were presented with were poets and philosophers who were representing themselves or representing what they thought to be a spiritual consciousness and that there wasn’t a sufficient input of social change ideas, even of the mainstream type much less of the Digger type.

Interviewer: I think it was Jerry Rubin who was the [unintelligible] for better or for worse as the spokesperson of those ideas of piecing all this together.

Peter Berg: So I don’t have to say much more than that, right?

Interviewer: (Laughs) I want to get back to [unintelligible] you might have of particular police.

Peter Berg: What do you mean?

Interviewer: Do you remember anyone in particular that stood out for you as a nemesis of the counterculture movement or The Diggers and what you were trying to do?

Peter Berg: The same police officer who hit Terence Hallinan in the head with a nightstick at San Francisco State was in the group of the San Francisco Tac Squad, the tactical squad, who finally arrested people [Diggers] on the City Hall steps and put Terence Hallinan in a police car at that event. It’s the same person. So San Francisco had a tactical squad, who was also called The Red Squad, that was commissioned to break up political demonstrations, to interfere with what could be called people’s events or progressive events or popular events—events without permits.

So rather than a particular individual, I think of the Tac Squad as being the police presence that we had to be dealing with.

Interviewer: You don’t remember a particular cop named Art Guerrins?

Peter Berg: Yeah, I do remember Guerrins.

Interviewer: What do you remember about him?

Peter Berg: Guerrins made a career out of arresting certain people. He arrested Emmett Grogan a number of times. He was a self-appointed vigilante who—most of the cases that he brought, by the way, were thrown out. He was the anti-drug cop on a personal crusade.

Interviewer: The Diggers talked a lot about no ego, you didn’t have leaders, nobody was giving a name to anything. What was that about – no ego, no identity, everybody was the same, no heroes here?

Peter Berg: During at least the first year of The Diggers, one of our tenets was that we would not be identified personally as personalities with what we were doing. And the reason for that was to get more people involved, and it works. If you don’t take credit for things, it’s amazing how fast somebody else will take credit for it or a number of people will decide it was their idea.

And if you want a progressive movement to gain currency fast, the best way to do it is to start activities that aren’t assigned with particular personalities—aren’t, uh…Stop that [ed.note stops the recording].

Male Voice: Yeah, you can say it.

Peter Berg: One of the best things you can do is to carry on activities without leaders so that people believe that they are empowered to do these things themselves, and once that starts, it really becomes a wildfire, so none of the Digger papers were signed for at least a year, maybe two years.

We would deliberately put people that had just come into the free store in front of the camera when they were being interviewed or we were being interviewed. I once introduced two reporters to each other as the manager of the free store just to watch what would happen and never identified myself as a person involved with the free store.

One of the cards in the free store read, “If somebody asks, ‘Who’s the manager?’ tell them, ‘You’re the manager.’”

Interviewer: What about the gender differences within the community and within The Diggers?

Peter Berg: There were notable women in The Diggers, and it was pretty well known who they were and what they did. We were all in a position of not being identified personally with what we were doing. So whether it was a man that did it or whether it was a woman that did it didn’t have a name associated with it so you really didn’t know. As far as what the roles were, I think during that time that to turn over our energy to help women—a poet, a tie-dyer, a chef, Digger bread-maker —accomplish what they wanted to do was indicative of relaxing gender roles.

If you were a Digger and were attempting to do something free, other people helped you, and in that sense it didn’t matter whether you were a woman or a man, and I can say that truthfully. As far as whether women were treated different than they were in the counterculture in general, I wouldn’t go that far. And I don’t think it was particularly—it was pre-women’s liberation. So expectations about women were the same as they were in the rest of the counterculture. But obviously it was—if you’re going to say free and leave it wide open that way, you were going to get free women, you were going to get free gays, you were going to get free artists of all kinds, and I never felt any resistance with that. Personally, I think it was a pre—a predecessor. The Diggers and the Haight-Ashbury in general were a kind of a preceding stage for movements that followed that; it was particularly ecology but women and gays as well.

Interviewer: Since we’re on free, the idea of free love, free relationships, how did that manifest itself for The Diggers and, from your perception, for the Summer of Love and the whole counterculture?

Peter Berg: How did free love manifest itself?

Interviewer: What does free love mean to you?

Peter Berg: Free love means not having obligatory requirements of sexual relationships—that because you make love with someone doesn’t mean that that person is obliged to you and you’re not obliged to them as a result of that. And was that a prevalent attitude in The Diggers? It was; it definitely was a prevalent attitude in The Diggers and with the communal groups that The Diggers were associated with—Black Bear Ranch which was notably sexually free, Morning Star Ranch.

Interviewer: Morning Star was important…

Male Voice: Before you move on, do you want to touch up on the subject of gays? Was that an issue in the community? Did it have any law? Was it discussed?

Peter Berg: I think the issue or the – let me start again. (Clears throat)

If there was a signal event for the way gays were treated in the Haight-Ashbury, it was the fact that the Haight Theater, which was known as a theater with gay overtones—that had shown films that were quote “gay films” —was taken over by new management, younger people who felt it was necessary to rename the Haight Theater, because of its previous reputation, the Straight Theater. That rather than being the gay theater that the Haight had been, that it would now be the Straight Theater. And what was really polarizing about that is that people that attended the theater or were involved with it resented that change and thought of the new management as being wrong-headed. Kenneth Anger, the gay filmmaker, had shown some of his films there as the Haight Theater and then was invited to show them as the Straight Theater and put a curse on it for being anti-gay. And that to me is really typical of the kind of reaction people had.

There was a growing acceptance of gay people. One of the underground newspapers that came out of the Haight-Ashbury, I forget the name of it, but love was in it somewhere, was a gay newspaper. And Chester Anderson, who was in charge of the Communications Company was gay. More open gayness was going on. The Kaliflower Commune; the Angels of Light grew out of connections with the Haight-Ashbury. And all of those are mainstays in early, overt gay behavior in San Francisco.

Interviewer: What about the way the people were dressing and men growing their hair long and the gender lines being blurred in some ways or traditional gender images?

Peter Berg: The more romanticized costumes that men were wearing—long hair, beads, earrings were more gender-bending than they had been previously.

Interviewer: When you stepped into that question, I was going somewhere and now I forget what it was.

Male Voice: The Morning Star.

Interviewer: Oh yeah, thank you.

Peter Berg: What is it?

Interviewer: Tell us about the relationship between The Diggers and Morning Star Ranch because it was an important one and important to a lot of people.

Peter Berg: The Diggers had a natural affinity with Morning Star Ranch because Morning Star Ranch had come to symbolize a place where ownership was not going to be personified. In other words, it wasn’t going to be a owner of Morning Star Ranch. In fact Lou Gottlieb turned the deed over to God so that the kind of society that they were acting out—the communal society of Morning Star Ranch was a variation on the urban Haight-Ashbury based Digger phenomenon.

And there was a lot of interchange between both places.

Interviewer: A lot of people said they came to think of Morning Star as The Digger Ranch—that there was this [unintelligible] relationship where they came up to get apples, brought food back to the city. Can you tell us about that a little bit?

Peter Berg: You know that I’m not really comfortable talking about that because in my mind what happened after 1968 was that a lot of the former Diggers went to a ranch in the Siskiyou Mountains named Black Bear Ranch, and that’s where more of my associations are.

Interviewer: Okay.

Peter Berg: And I have as many associations with Olompali as I do with Morning Star Ranch.

Interviewer: Okay, that’s fine. This is a jump in concept – the [Haight] Street riots that we’ve heard talked about – a lot of people say they were instigated to happen as a form of destruction maybe caused by The Diggers, maybe caused by random acts of destruction on the street. What were they to you?

Peter Berg: A riot is a form of street theater from Digger perspective. And I was happily involved with two riots that were started by us to be riots. Both started as theater events. One was to close down the street and have the police arrest the people that were instigating that and the other was to have the police arrest Hell’s Angels during the celebration up and down the street.

I know of other people that caused disruptions of traffic. The reason was that we were getting overwhelmed by tourist buses full of people who just drove up and down the street gawking at people. We thought the Haight-Ashbury was our neighborhood.

Interviewer: Say that one again.

Peter Berg: A strong element in disrupting traffic and starting riots that closed the street was that there were tour buses at that time, a lot of them, and tourists and automobiles that patrolled up and down the streets gawking at what was going on. And to bring attention to this and to show our opposition to it, we would close the street. I mentioned there were at least six occasions when the streets were closed by one event or another.

Interviewer: You had just said that when the bus came you thought the community was ours. Can you just give us that line so we have it [unintelligible]?

Peter Berg: We thought the community was ours.

Interviewer: There was a communication bulletin, I think that Chester Anderson wrote, that was entitled something like, “Uncle Tim’s Cabin.” It was very derogatory of this scene and how things really were deteriorating. It had a line in it something like, “Come to the Haight-Ashbury—tune in, turn on and drop dead” was one of the lines in it that when girls were getting raped. Do you have any recollection of that bulletin and what he was talking about in it?

Peter Berg: Toward the end of 1968, the situation in the Haight-Ashbury had deteriorated I believe as much through police presence as through other reasons other[s]…attributed to it—such as hard drugs, or elements coming in that are trying to deal drugs, or criminal elements, and so forth. It had [deteriorated]. The bloom was off the rose and people weren’t coming to the Haight-Ashbury the way they had previously. During that time, there were several people who took note of it. Michael McClure wrote a poem about it. The Communications Company put out a broadside. Probably by the end of 1968, the Haight-Ashbury phenomenon as it had been in its flower had passed.

Interviewer: In terms of the summer itself, the blossoming summer of ‘67, and I might be wrong about this, I thought a particular bulletin came out toward the end of the summer.

Peter Berg: The what?

Interviewer: The summer of ‘67—that bulletin I was describing—not ‘68. Were you aware of things deteriorating that much during the Summer of Love itself?